In the shadow of Bach and Liszt

by Adrian Cho

Day 10 was another packed one, and we aimed to get a nice early start. Evan and Meg started the day off right by grabbing coffee and bagel right down the street—from the appropriately named Coffee Fellows and Bagel Brothers. The rest of us slow risers (myself included) made do with leftovers from last night. The drive to Naumburg through the German countryside was a quiet one. Given our vigorous visiting schedule and the late nights we’ve been keeping, we were all too grateful for a few extra moments of shut-eye. Selig sind die Chris’s, who had both been chauffeuring us around the whole trip!

The spire of St. Wenzel, Naumburg.

Enjoying a moment in the sun before attending the organ concert in Wenzelkirche.

We made it to Naumburg a little before noon. Sun shone brightly overhead as we got out of the car, summer blaze fully upon our necks. We quickly made our way to St. Wenzel's, well in time for the noontime organ recital. St. Wenzel's housed one of the three instruments on our itinerary for the day: a 1746 Hildebrandt. We also planned to visit another instrument at Marien-Magdalenen-Kirche in Naumburg. Since we had five whole hours with both instruments, we decided to split into two smaller groups and swap locations halfway through.

1746 Hildebrandt Organ, St. Wenzelkirche, Naumburg.

1869 Ladegast Organ, Marien-Magdalenen-Kirche, Naumburg.

Adrian Cho plays the 1869 Ladegast Organ, Marien-Magdalenen-Kirche, Naumburg.

Jennifer, Chris Porter, Meg, Evan, and I trekked to Marien-Magdalenen, home to an 1869 Ladegast. The Ladegast was a smaller instrument than the Lütkemüller we saw in Seehausen and the more famous Ladegast in Merseburg we would see later that day. Despite its smaller size, it was a compact and coherently designed instrument; it really had all the stops it needed. The organ responded beautifully when Meg played Organ Sonata No. 1 by Hindemith, and we took our turns playing our Romantic repertoire. I had fun with Brahm's chorale prelude “Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele.” It was an interesting registrational challenge to put the soprano chorale melody in the pedal, when the high E was missing from the compass!

After a while, my group headed over to St. Wenzel's to try our hands on the Hildebrandt organ. Completed by Zacharias Hildebrandt in 1746 and restored in late 90's, the organ, with its 52 stops, was a wonderful example of a large, German Baroque instrument. Hildebrandt himself had a distinguished pedigree, having apprenticed under the famed organ builder Gottfried Silbermann. The instrument was inspected and certified in 1746 by both Johann Sebastian Bach and Silbermann. An idiosyncratic feature of the organ was the paper labeling on the stop knobs. The labels are originals from 18th century and forbidden from direct contact by hand lest they crumble away. Possibly, traces of J. S. Bach's fingerprints linger still on some of them!

Original stop knob on the 1746 Hildebrandt Organ, St. Wenzelkirche, Naumburg.

We sat down and got underway. As one might expect, we had a great time trying out all of our various Bach pieces. The divisions worked well in concert, with mixtures blending beautifully together. One disorienting feature was the large pedal towers directly to the either side of the console, which sometimes made it difficult to hear the manual parts when playing with full plenum. The Hildebrandt also boasted some wonderfully warm and ethereal string stops, which reminded me of the Bielfeldt organ back in Stade.

Console detail, 1746 Hildebrandt Organ, St. Wenzelkirche, Naumburg.

Our two and half hours was up all too soon, and we reluctantly relinquished our precious time with this marvelous instrument. Before we bade farewell, Meg and Evan noticed that the color of the console was almost exactly the same shade of blue as the covers of Bärenreiter's New Bach Edition publications! We idly wondered whether that was a conscious choice by the publishing house, paying homage to the connection between the organ and the great composer.

Merseburg Dom.

For our final destination, we drove 50 minutes due north to Merseburg. Merseburg Cathedral was a sight to behold, tracing its lineage all the way back to the Middle Ages. The cathedral counted Martin Luther among its celebrity guests, who gave a sermon there in 1545.

It is also home to an 1855 Ladegast, an organ of renown. This Ladegast is a huge German Romantic instrument, including a large number of flue stops. Possessing an incredible dynamic range, it is capable of creating seamless crescendos and decrescendos from pp to ff. For complex pieces, it requires at least three assistants working in concert; one on each side to pull the stops and another to turn pages. One particularly interesting stop is its 16' Aeoline on the Brustwerk. It is very rare to find this soft, freely vibrating reed stop at the 16' pitch level, which both Liszt and Reubke specifically ask for in their works.

1855 Ladegast Organ, Merseburg Dom.

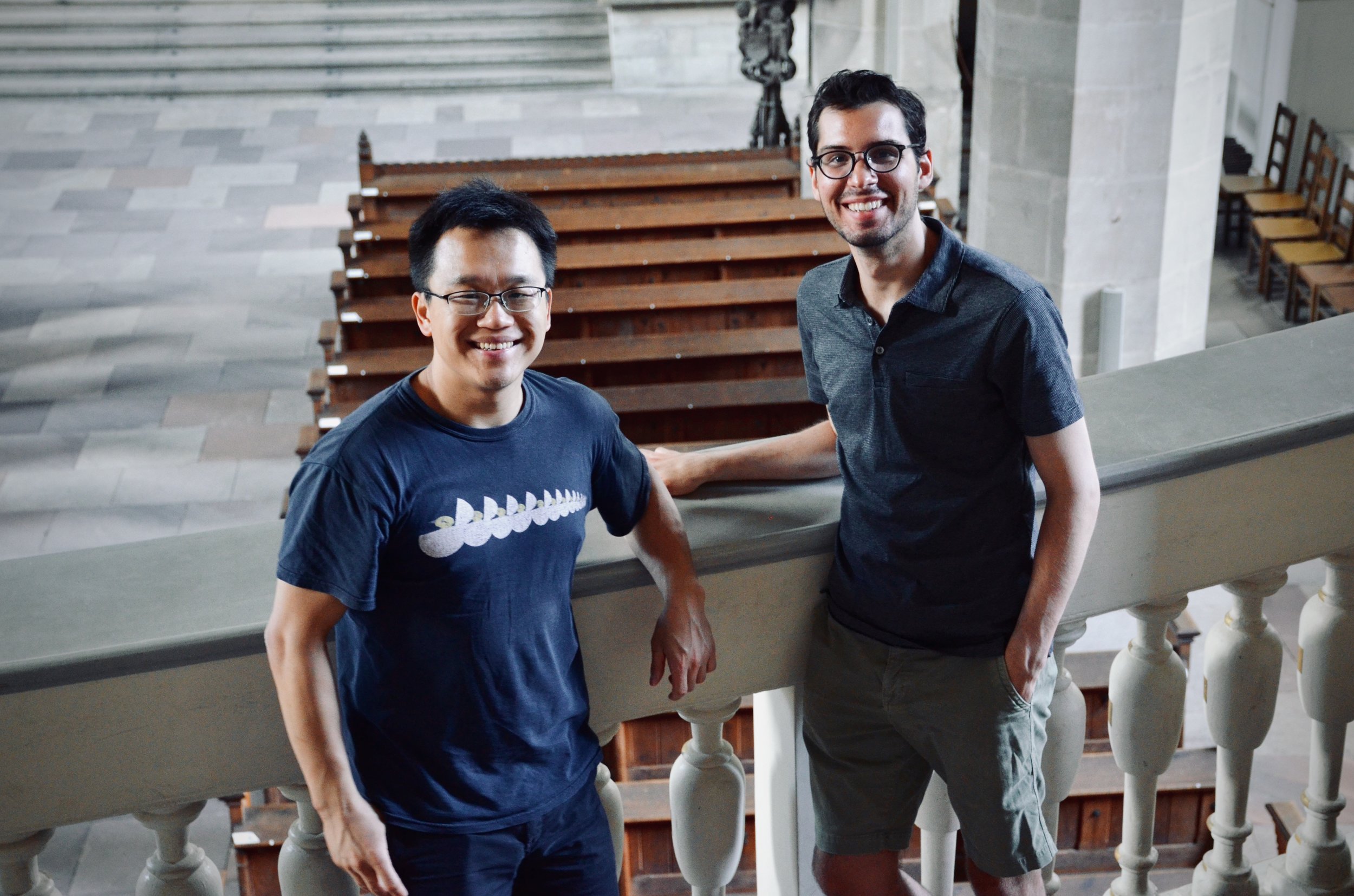

Nicholas Capozzoli performs Liszt’s “Ad nos…” on the 1855 Ladegast Organ in Merseburg Dom.

This organ also has an important historical place in German Romantic organ repertoire. Liszt had planned to premiere Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H for its inauguration. The piece was not ready in time, however, and another of Liszt's pieces, Fantasy and Fugue on "Ad nos, ad salutarem undam", was played instead. Finally, Julius Reubke, a student of Liszt who died young, also premiered his Sonata on the 94 Psalm on this instrument. Reubke calls for the aforementioned 16' Aeoline in his piece. We were in for a treat, as Nick and Jennifer played superbly Liszt's Ad nos and Reubke’s Sonata, respectively.

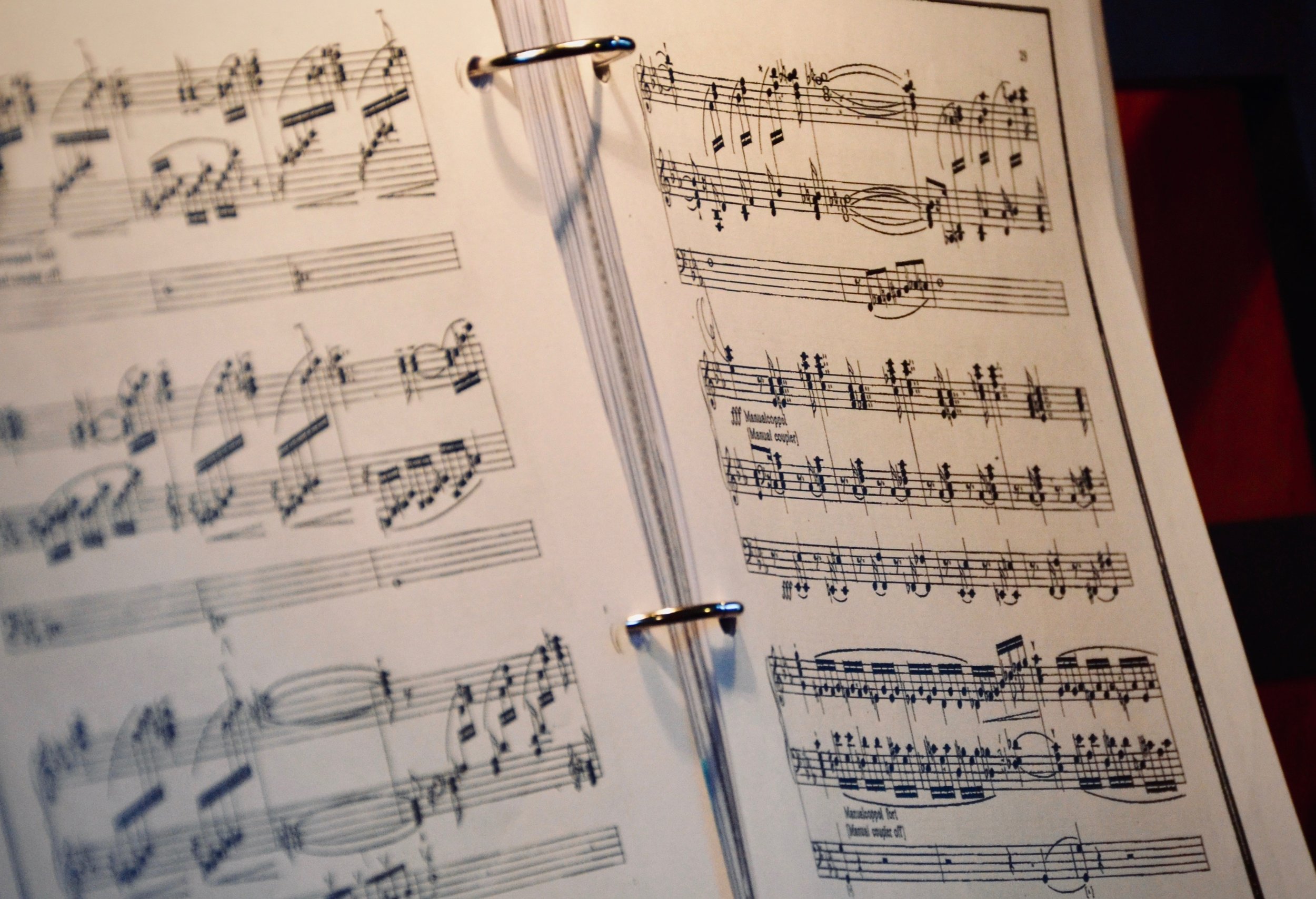

The score of Julius Reubke’s Sonata, which was written for, and premiered on, this 1855 Ladegast Organ, Merseburg.

We went up to play one by one, bringing our best performance pieces. I took my turn at the bench, aiming to play Bach's Prelude and Fugue in A minor, and was stupefied. Such heavy key action! It really took an unexpected amount of strength to press down on the keys. Alex Ross, our resident organ builder, explained to me that the heaviness results from excessive friction in the various mechanical connections from the key to the pallet, which is not generally an intended part of modern action design. It made for good point of reflection however, as I had to figure out on the fly how I could use my arm weight more efficiently. Food for thought when I practice back home!

Per routine, we returned to our abode in Leipzig late and had our rooftop dinner. As the sun passed into darkness near midnight, we settled in to prepare ourselves for the last day of our tour.

A stunning evening on the roof top, with the spire of Nikolaikirche, Leipzig.