Our last day in Leipzig

by Nick Capozzoli

It’s hard to believe this is the last day of our tour! Although our schedule was packed, the days seemed to pass quickly. I’ve enjoyed playing some of Germany’s best instruments—everything from Renaissance to high Romantic organs—as well seeing (and tasting) beautiful aspects of German culture! While most days focused on a specific time period, our final day featured three very different organs.

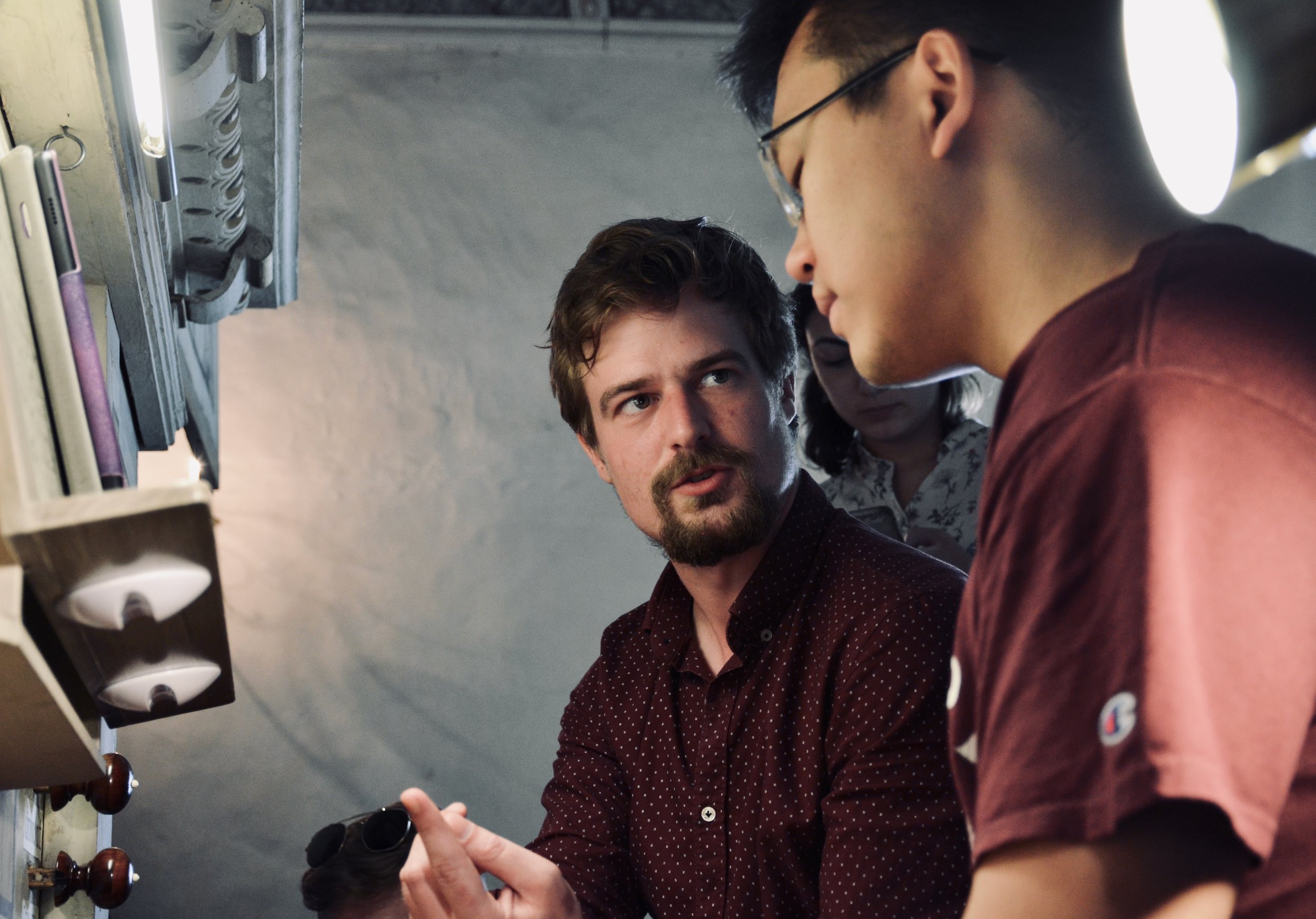

We began in Leipzig at the Michaeliskirche. It was refreshing to drive only 10 minutes to make our morning appointment—a rarity for this trip! There, we met organist Martin Sturm, a teaching assistant at the Hochschule für Musik in Leipzig. Martin was our host for the entire day; he was extremely generous with his time and shared a wealth of expertise.

Martin Sturm demonstrates for Evan Currie on the 1904 Sauer Organ, Michaeliskirche, Leipzig

1904 Sauer Organ, Michaeliskirche, Leipzig

This venue is quite special, as both the church and its organ were built at the turn of the twentieth century. I think they complement each other quite well. The church is a composite of many architectural styles (Renaissance, neo-Baroque, neo-Gothic, etc), and this Wilhelm Sauer organ is equally kaleidoscopic. No single stop is particularly stunning, although it is important to remember that such instruments do not function like the French or English ones with which we are familiar. The 8’ and 4’ stops are relatively dull on their own, but when combined, they make a huge, unified mass of sound. I’ve never heard a smoother transition from ppp (the softest whisper) to fff (an apocalyptic roar). North Americans are also used to powerful reeds that serve as the final step in a crescendo. The reeds are few in number and relatively weak on Sauer organs. Instead, the tutti (full organ) harnesses strength in rich foundations capped by mixtures and cornets.

Nick Capozzoli plays the 1904 Sauer Organ, Michaeliskirche, Leipzig

With three hours on this instrument, the group played a variety of repertoire to experiment with its features. Evan and I tried out works by Max Reger, a composer who certainly played and approved of Sauer organs. Evan’s performance of Benedictus, op. 59 showed off its warm foundations and ethereal strings, while my run-through of the Fantasy and Fugue in D minor, op. 135b showcased the Sauer’s seamless crescendi and diminuendi. Martin constantly ran between both sides of the console to pull stops, although we also had a unique mechanism at our disposal: a Rollschweller.

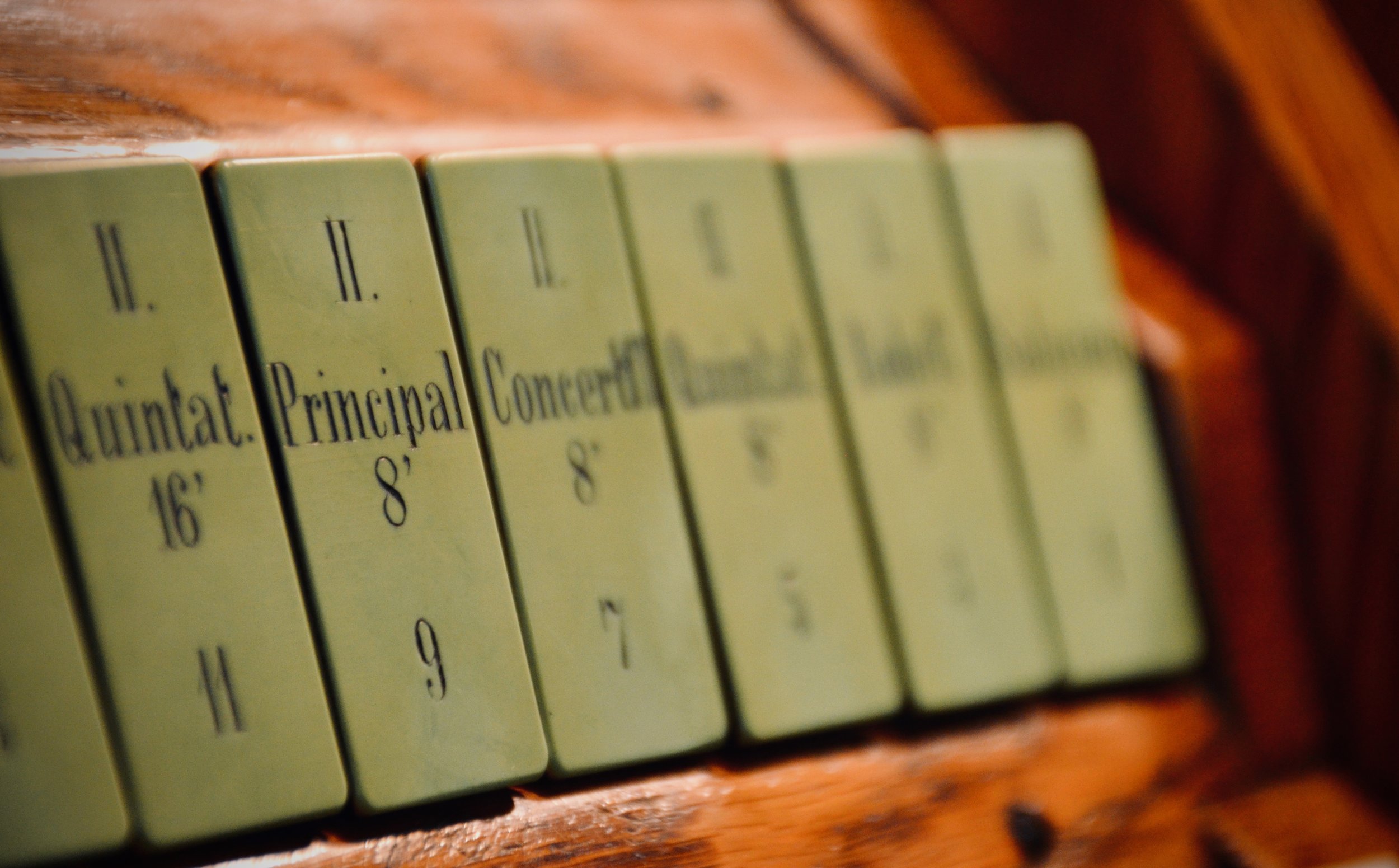

The Rollschweller of the 1904 Sauer Organ, Michaeliskirche, Leipzig

The device is a wheel and axle, and when turned toward the organist, stops are added indefinitely. Conversely, one can make a decrescendo by spinning the wheel away from them. This Rollschweller is often necessary in the music of Reger and his contemporaries. The frequency and wide spectrum of dynamic contrast demanded is a strenuous workout for assistants! This “crescendo pedal” saves so much time and allows the player to modify the sound at his or her discretion.

Martin Sturm assists Meg Cutting at the 1904 Sauer Organ, Michaeliskirche, Leipzig

Next, Jennifer gave a repeat performance of Reubke’s Sonata on the 94th Psalm, a fascinating experiment in the difference between early Romantic instruments (the Ladegast from last night) and later ones (this Sauer organ). Although we’ve played Bach’s music on period instruments during this trip, Martin reminded us that with a modified approach, this repertoire works quite well on Sauer organs. Alexander Straus-Fausto played the Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543. The Rollschweller gave this piece much sonic power, while Alex’s incorporation of Romantic playing techniques (legato and overlegato) made sense on this instrument.

Listen here to two different versions of the same piece, as performed by Alexander Straus-Fausto. The first is on the romantic Sauer organ, the second on the baroque Silbermann organ (which Bach might have played). Hear the different techniques employed and the effects they create.

Martin Sturm welcomes members of Boston Organ Studio to Pomßen, Germany.

After a quick sandwich, we drove to the quaint town of Pomßen. The village’s tiny Wehrkirche has so much history. It dates from the 13th century, and its cross is one of few extant 13th-century crosses in Europe. While compact, the 1671 organ by Gottfried Richter is both visually stunning and sonically powerful (much to our surprise). It is composed of just 13 stops, but each sound sings beautifully into this space. We tried out several Renaissance and early Baroque pieces, experimenting with countless stop combinations.

1671 Richter Organ, Pomßen

Martin Sturm coaches Jennifer Hsiao on the 1671 Richter Organ, Pomßen.

1722 Gottfried Silbermann Organ, Bad Lausick

Our final appointment of the day (and trip) was at the Killianskirche in nearby Bad Lausick. The organ was built by Gottfried Silbermann (a familiar friend of ours now) in 1722 for a church in Saxony. In 1957, it was relocated to this parish and restored in 1988. Martin played fantastic improvisations to demonstrate the small, two-manual instrument. While we often speak of organs having a human and vocal quality, Martin noted this particular one’s instrumental character. The flues, especially the viola da gamba, sound like actual string instruments. Meg and I played variations to show off the instrument’s many colors: Johann Pachelbel’s Chaconne in F minor and Bach’s partita on “Ach, was soll ich Sünder machen,” respectively). Martin worked with Alexander Straus-Fausto on varying the speed and depth of key attack; when listening closely, these subtle tricks make a big difference in the sound. We certainly learned a lot today from Martin and these three instruments.

Members of Boston Organ Studio in Bad Lausick with Martin Sturm. Our last organ visit of the trip.

One last dinner on the roof deck.

We spent our last evening together over homemade pizza, lots of wine, and good conversation. Three new friends joined us: Xaver (one of our Hamburg hosts), Claudius Woehl (an organbuilder), and today’s leader Martin. Our scenic rooftop has been the location for many dinners and late-night hangouts, and we’ll certainly miss that. Although we’ll miss playing historic instruments, the friendships and professional contacts acquired over the past two weeks have made the trip totally worthwhile!